Notes

How to recognize max-flow problems? Often they are hard to detect and usually boil down to maximizing the movement of something from a location to another. We need to look at the constraints when we think we have a working solution based on maximum flow – they should suggest at least an O(N³) approach. If the number of locations is large, another algorithm (such as dynamic programming or greedy), is more appropriate.

If the problem description sugggest multiple sources and/or sunks. We can convert this to a network that has a unique source and sink. We can just add node(call it super-source) and add edge with infinite capacity to every source.

Say we have restriction of some node(say a city is only allowed some maximum amount of water), we can create an edge between two vertices with this capacity.

Maximum flow problems may appear out of nowhere. For example: “You are given the in and out degrees of the vertices of a directed graph. Your task is to find the edges (assuming that no edge can appear more than once).”

Solution: First, notice that we can perform this simple test at the beginning. We can compute the number M of edges by summing the out-degrees or the in-degrees of the vertices. If these numbers are not equal, clearly there is no graph that could be built. This doesn’t solve our problem, though. There are some greedy approaches that come to mind, but none of them work.

We will combine the tricks discussed above to give a max-flow algorithm that solves this problem.

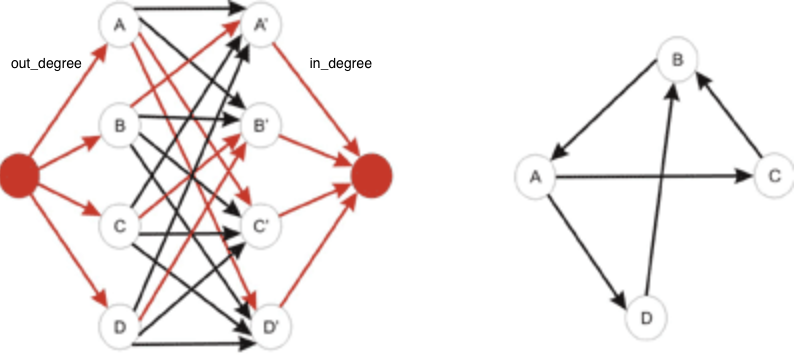

First, build a network that has 2 (in/out) vertices for each initial vertex. Now draw an edge from every out vertex to every in vertex. Next, add a super-source and draw an edge from it to every out-vertex. Add a super-sink and draw an edge from every in vertex to it. We now need some capacities for this to be a flow network.

For each edge drawn from the super-source we assign a capacity equal to the out-degree of the vertex it points to. As there may be only one arc from a vertex to another, we assign a 1 capacity to each of the edges that go from the outs to the ins. The capacities of the edges that enter the super-sink will be equal to the in-degrees of the vertices. If the maximum flow in this network equals M – the number of edges, we have a solution.

An example is given below where the out-degrees are (2, 1, 1, 1) and the in-degrees (1, 2, 1, 1).

Some other problems may ask to separate two locations minimally. Some of these problems usually can be reduced to minimum-cut in a network.

Let's try to find minimum-cut with the minimum number of edges. An idea would be to try to modify the original network in such a way that the minimum cut here is the minimum cut with the minimum edges in the original one.

- Notice what happens if we multiply each edge capacity with a constant T. Clearly, the value of the maximum flow is multiplied by T, thus the value of the minimum cut is T times bigger than the original. A minimum cut in the original network is a minimum cut in the modified one as well.

- Now suppose we add

1to the capacity of each edge. Is a minimum cut in the original network a minimum cut in this one? The answer is no, see the below figure, take T = 2, each edge weight will beT*e + 1.

Why did this happen? Take an arbitrary cut. The value of the cut will be T times the original value of the cut, plus the number of edges in it. Thus, a non-minimum cut in the first place could become minimum if it contains just a few edges. This is because the constant might not have been chosen properly in the beginning, as is the case in the example above.

We can fix this by choosing T large enough to neutralize the difference in the number of edges between cuts in the network. In the above example T = 4 would be enough, but to generalize, we take T = 10, one more than the number of edges in the original network, and one more than the number of edges that could possibly be in a minimum-cut.

It is now true that a minimum-cut in the new network is minimum in the original network as well. However the converse is not true, and it is to our advantage. Notice how the difference between minimum cuts is now made by the number of edges in the cut. So we just find the min-cut in this new network to solve the problem correctly.

Min-cut pattern

Let’s illustrate some more the min-cut pattern: “An undirected graph is given. What is the minimum number of edges that should be removed in order to disconnect the graph?” In other words the problem asks us to remove some edges in order for two nodes to be separated. This should ring a bell – a minimum cut approach might work.

We are not asked to separate two given vertices, but rather to disconnect optimally any two vertices, so we must take every pair of vertices and treat them as the source and the sink and keep the best one from these minimum-cuts.

An improvement can be made, however. Take one vertex, let’s say vertex numbered 1. Because the graph should be disconnected, there must be another vertex unreachable from it. So it suffices to treat vertex 1 as the source and iterate through every other vertex and treat it as the sink.

What if instead of edges we now have to remove a minimum number of vertices to disconnect the graph?

Now we are asked for a different min-cut, composed of vertices. We must somehow convert the vertices to edges though. Recall the problem above where we converted vertex-capacities to edge-capacities. The same trick works here.

- First “un-direct” the graph as in the previous example -- we can direct the graph by replacing every (undirected) edge x-y with two arcs: x-y and y-x.

- Next double the number of vertices and deal edges the same way: an edge x-y is directed from the out-x vertex to in-y.

- Then convert the vertex to an edge by adding a 1-capacity arc from the in-vertex to the out-vertex. Now for each two vertices we must solve the sub-problem of minimally separating them. So, just like before take each pair of vertices and treat the out-vertex of one of them as the source and the in-vertex of the other one as the sink (this is because the only arc leaving the in-vertex is the one that goes to the out-vertex) and take the lowest value of the maximum flow. This time we can’t improve in the quadratic number of steps needed, because the first vertex may be in an optimum solution and by always considering it as the source we lose such a case

Flow Graph Modeling

- Recognizing that the problem is indeed a Network Flow problem(this will get better after you solve more Network Flow problems).

- Constructing the appropriate flow graph (i.e. if using our code shown earlier: Initiate the residual matrix res and set the appropriate values for ‘s’ and ‘t’).

- Running the Edmonds Karp’s code on this flow graph.

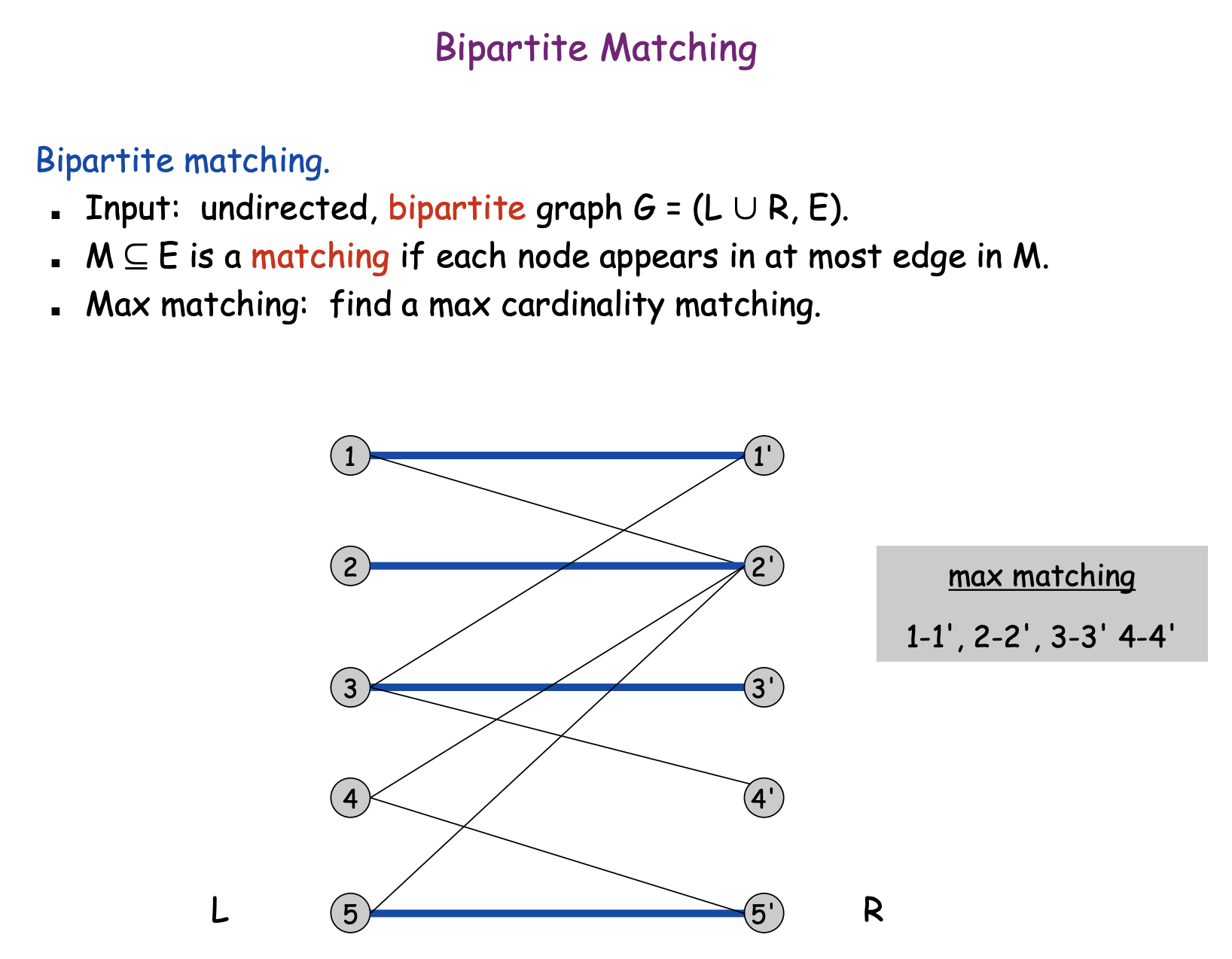

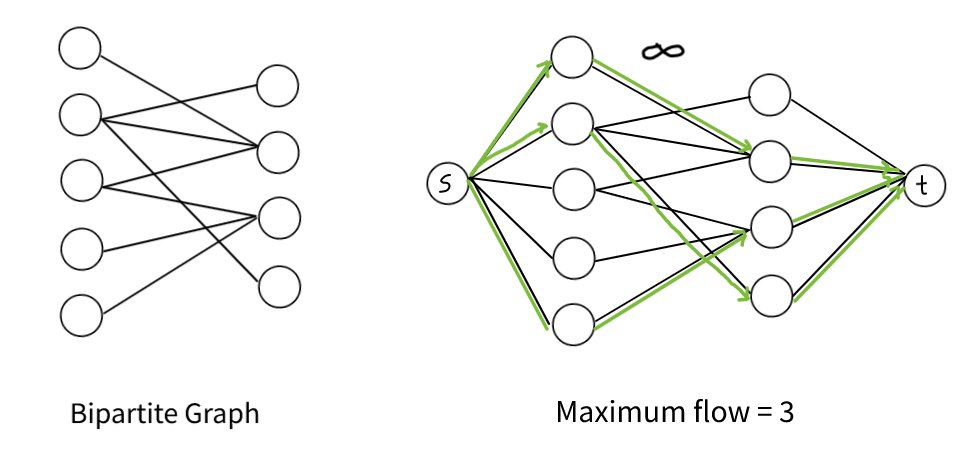

Bipartite matching

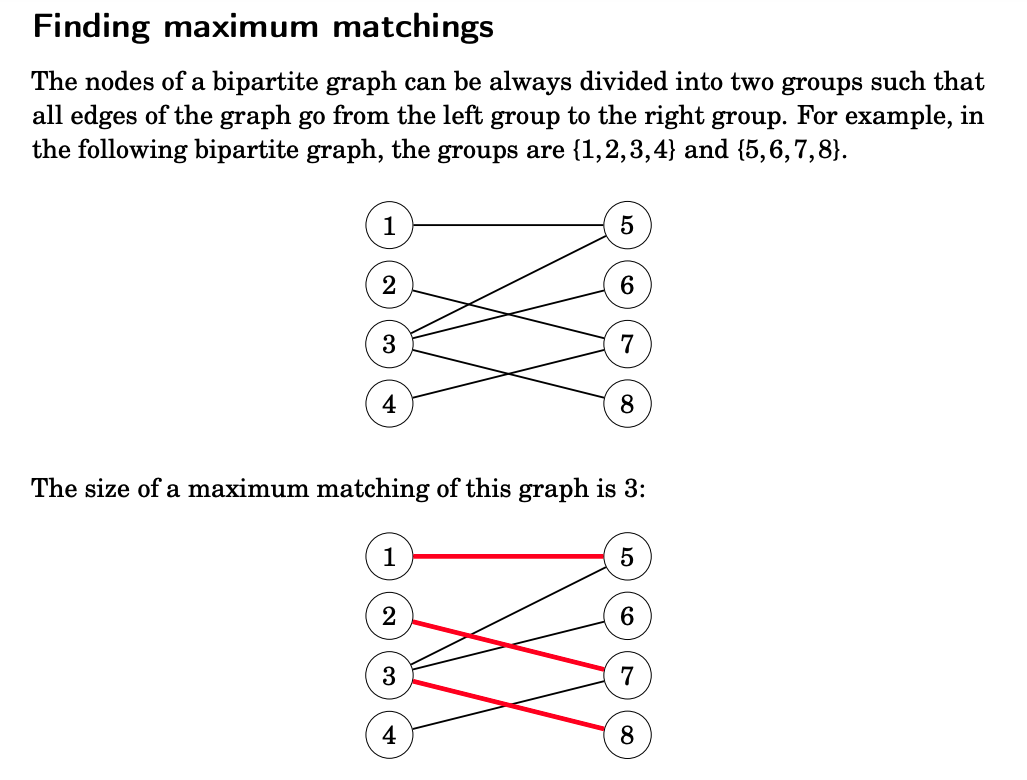

The maximum matching problem asks to find a maximum-size set of node pairs in an undirected graph such that each pair is connected with an edge and each node belongs to at most one pair.

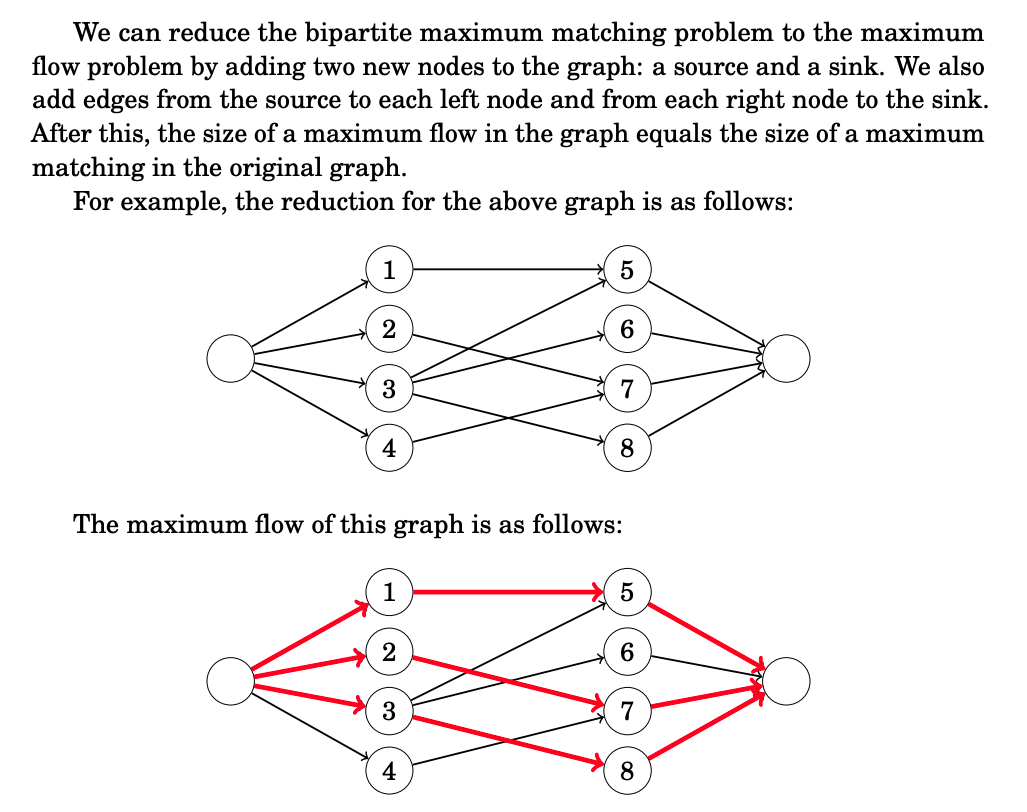

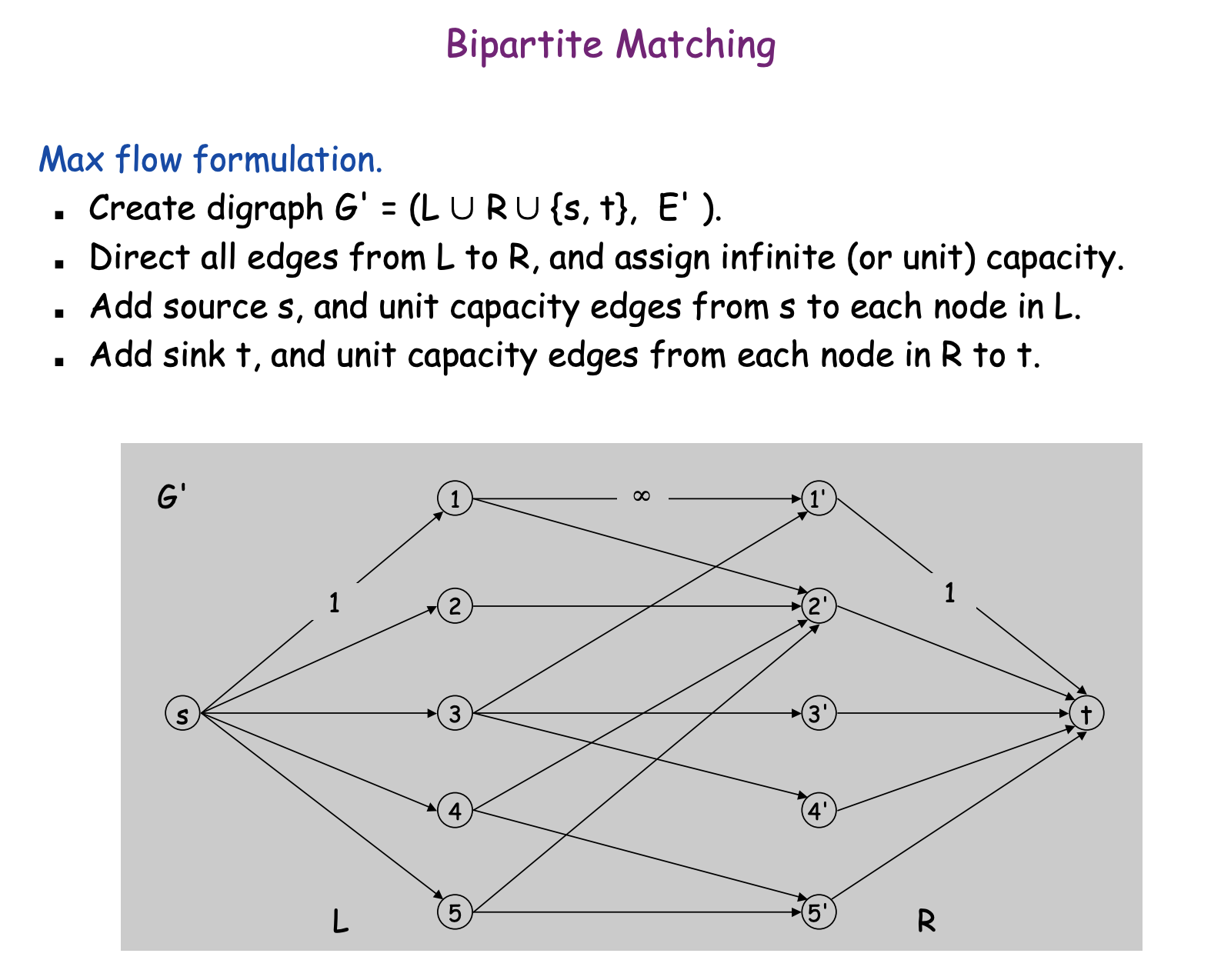

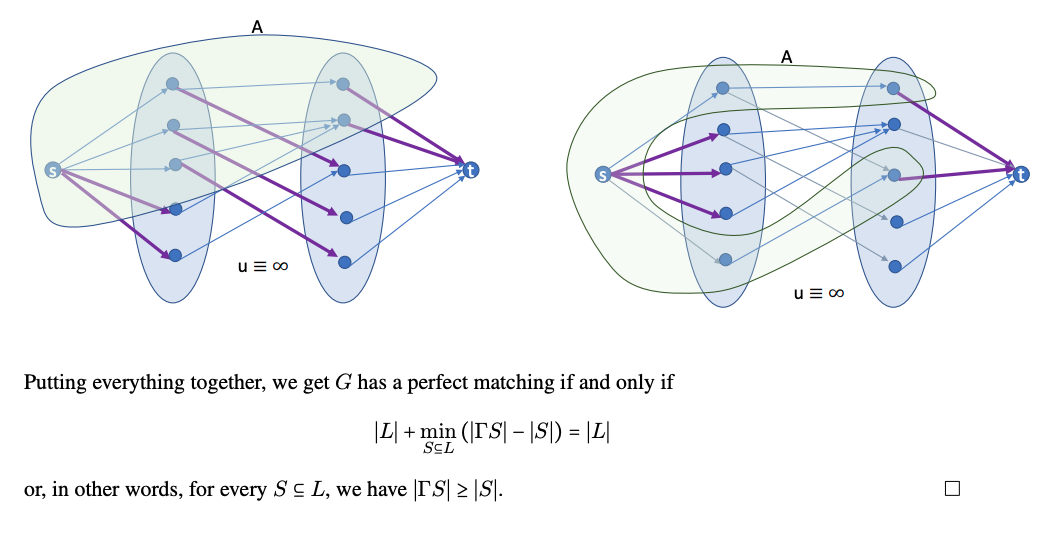

There are polynomial algorithms for finding maximum matchings in general graphs, but such algorithms are complex and rarely seen in programming contests. However, in bipartite graphs, the maximum matching problem is much easier to solve, because we can reduce it to the maximum flow problem.

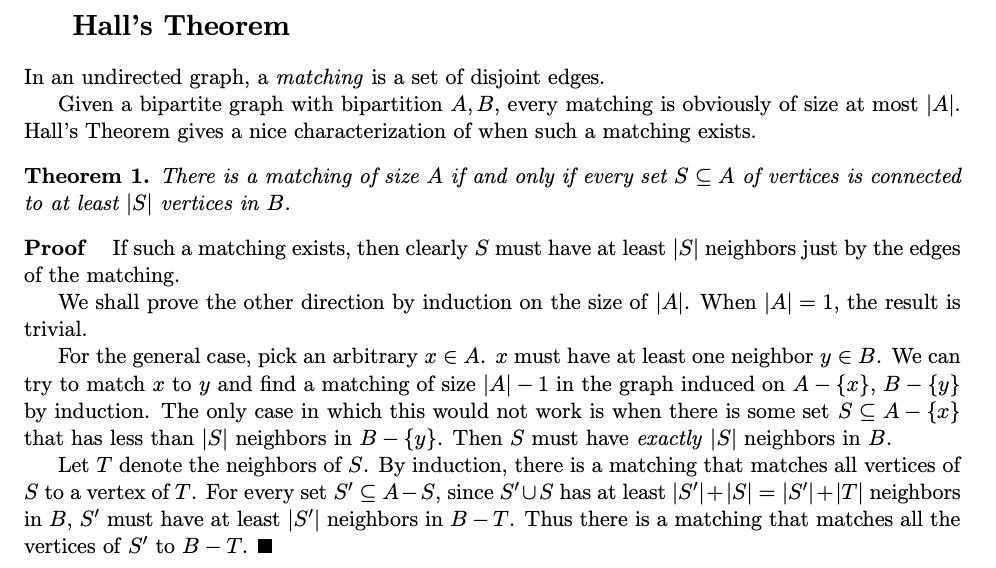

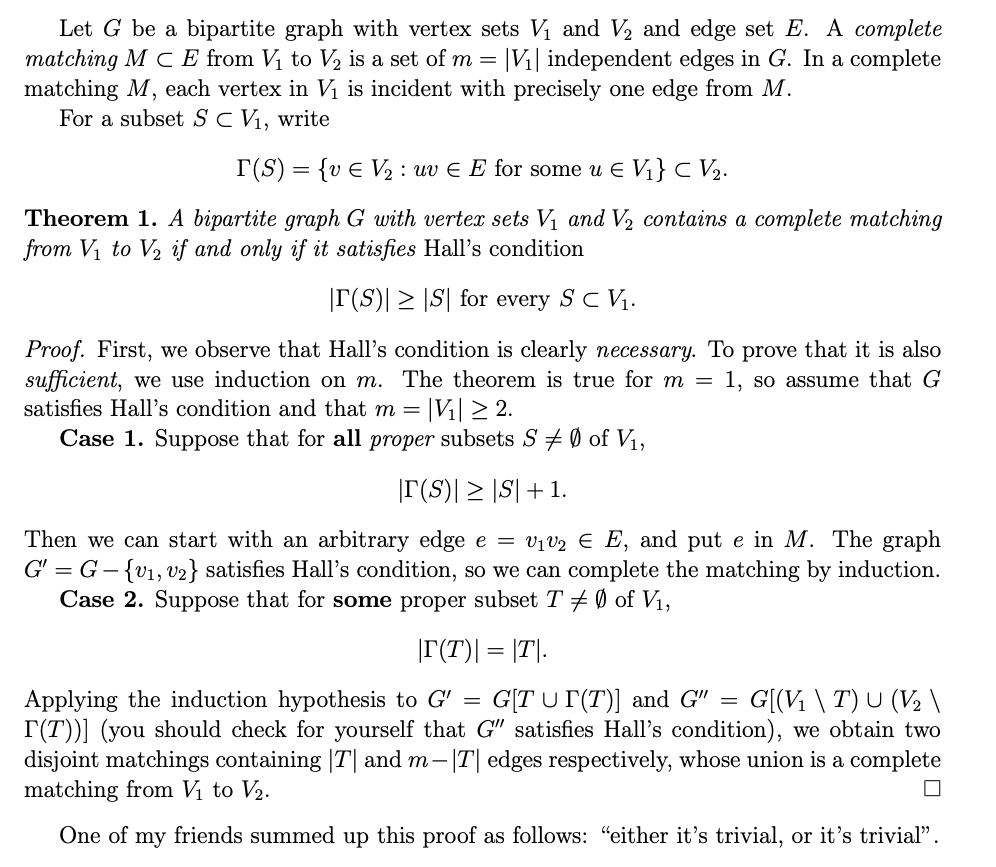

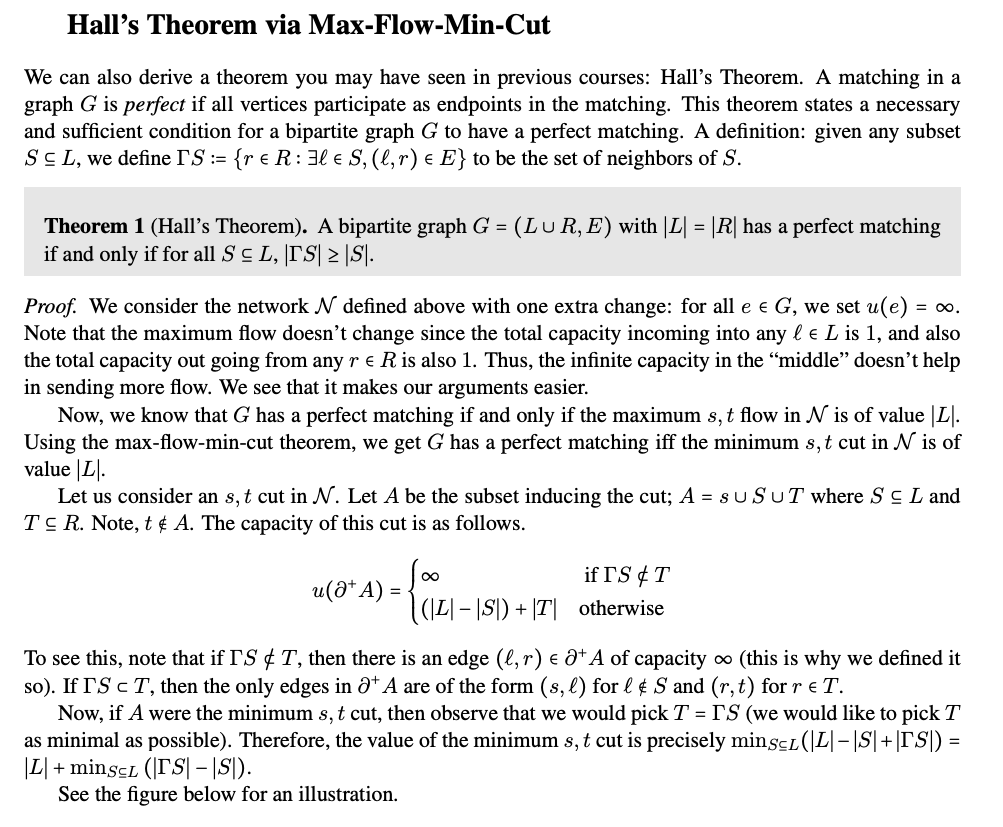

Hall’s theorem can be used to find out whether a bipartite graph has a matching that contains all left or right nodes. If the number of left and right nodes is the same, Hall’s theorem tells us if it is possible to construct a perfect matching that contains all nodes of the graph.

Vertex Cover in Bipartite Graphs

- A vertex cover in a graph is a set of vertices that includes at least one endpoint of every edge, and a vertex cover is minimum if no other vertex cover has fewer vertices.

- A matching in a graph is a set of edges, no two of which share an endpoint, and a matching is maximum if no other matching has more edges.

- It is obvious from the definition that any vertex-cover set must be at least as large as any matching set (since for every edge in the matching, at least one vertex is needed in the cover).

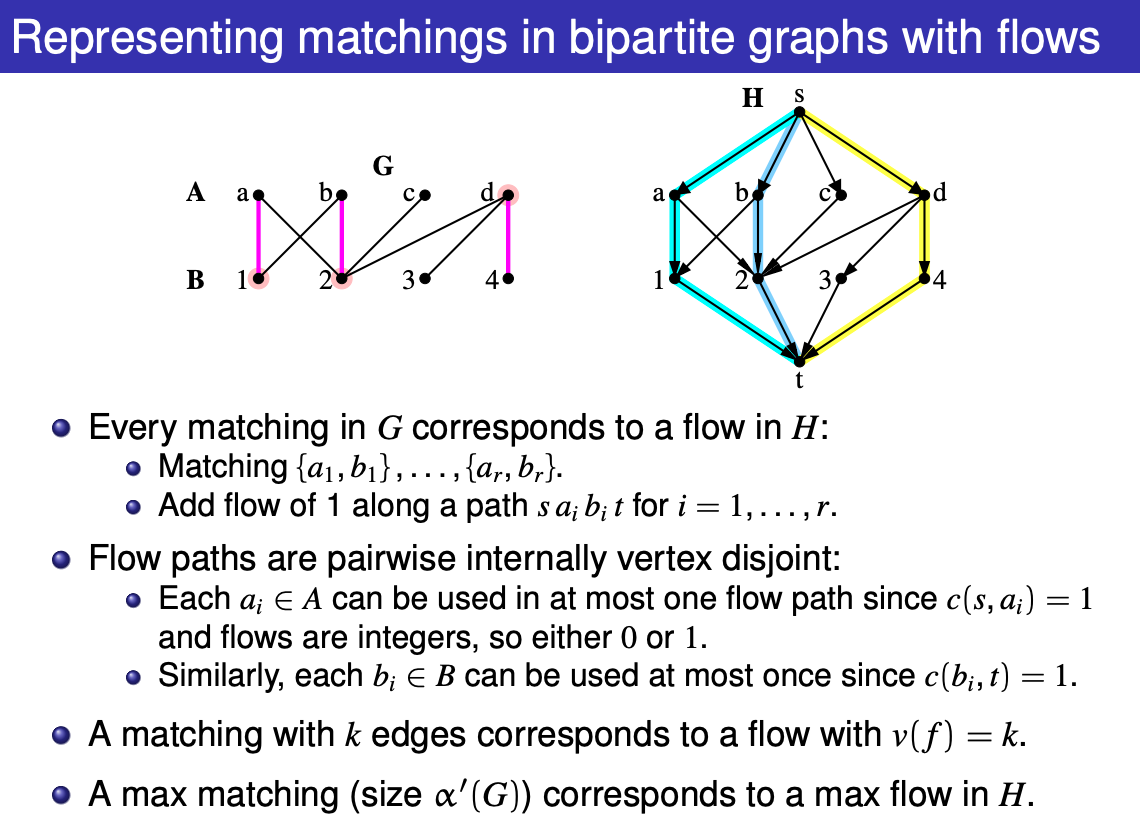

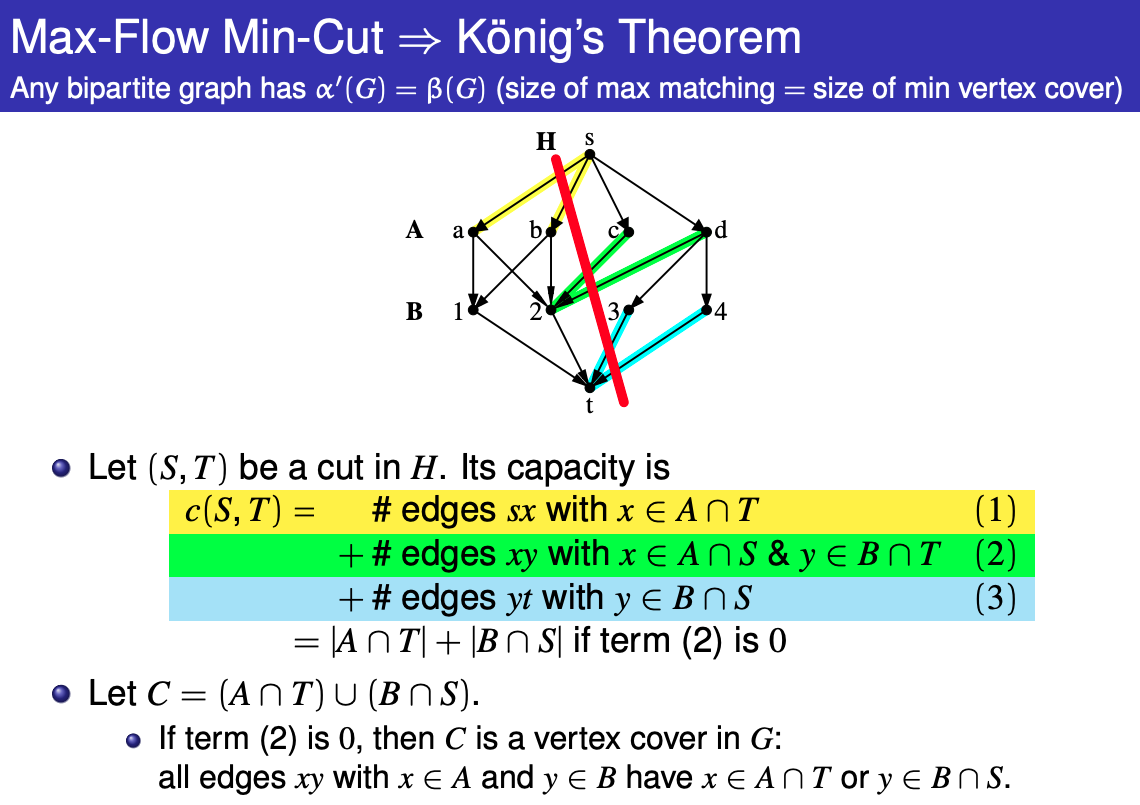

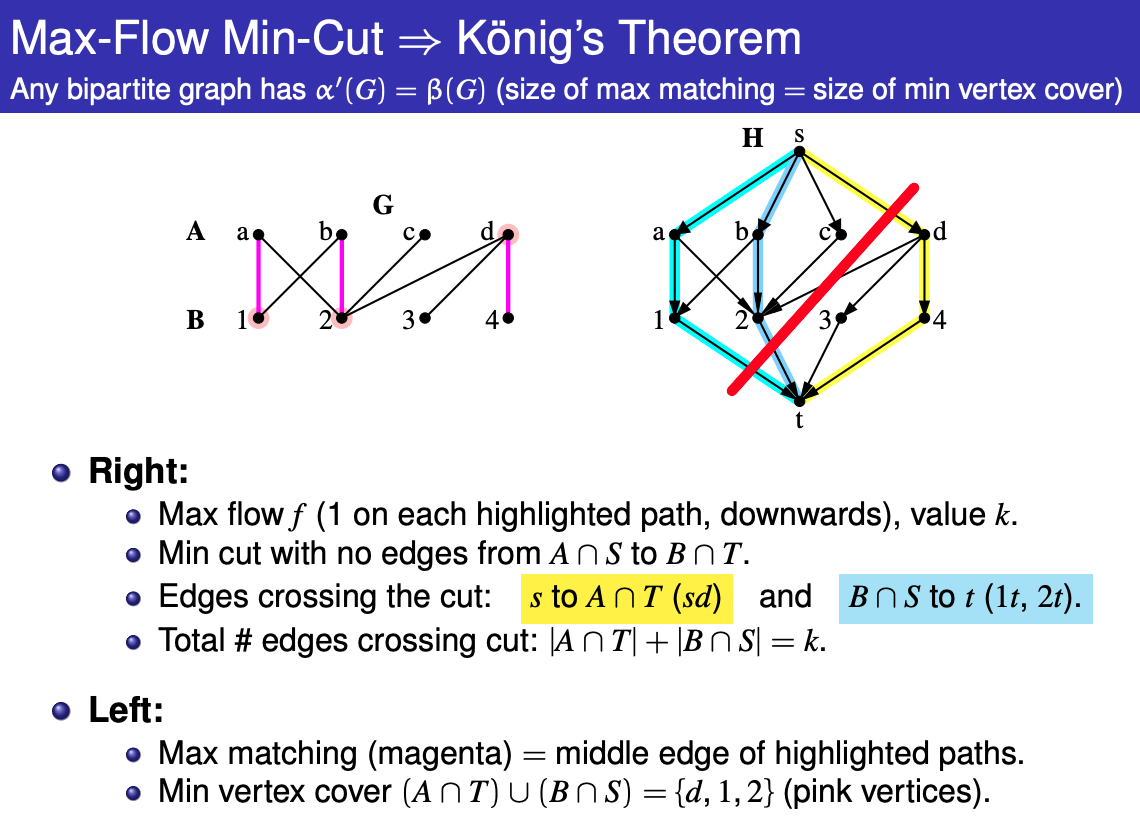

- In particular, the minimum vertex cover set is at least as large as the maximum matching set. Kőnig's theorem states that, in any bipartite graph, the minimum vertex cover set and the maximum matching set have in fact the same size.

Kőnig’s theorem

A minimum node cover of a graph is a minimum set of nodes such that each edge of the graph has at least one endpoint in the set. In a general graph, finding a minimum node cover is a NP-hard problem. However, if the graph is bipartite, Konig’s theorem ˝ tells us that the size of a minimum node cover and the size of a maximum matching are always equal. Thus, we can calculate the size of a minimum node cover using a maximum flow algorithm.

Example:

Let G = (V,E) be a bipartite graph and let L, R be the two parts of the vertex set V. Suppose that M is a maximum matching for G. No vertex in a vertex cover can cover more than one edge of M (because the edge half-overlap would prevent M from being a matching in the first place), so if a vertex cover with |M| vertices can be constructed, it must be a minimum cover.

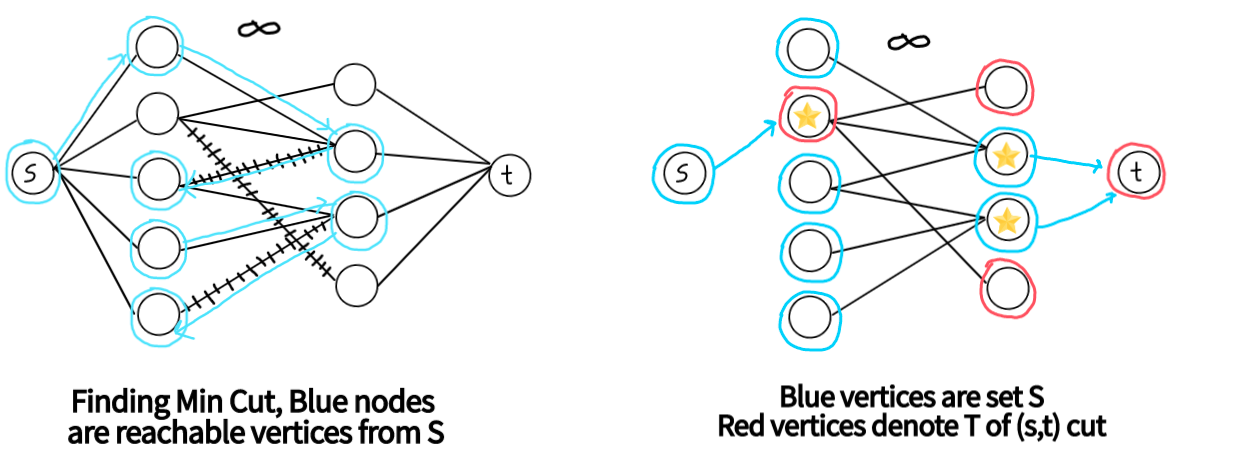

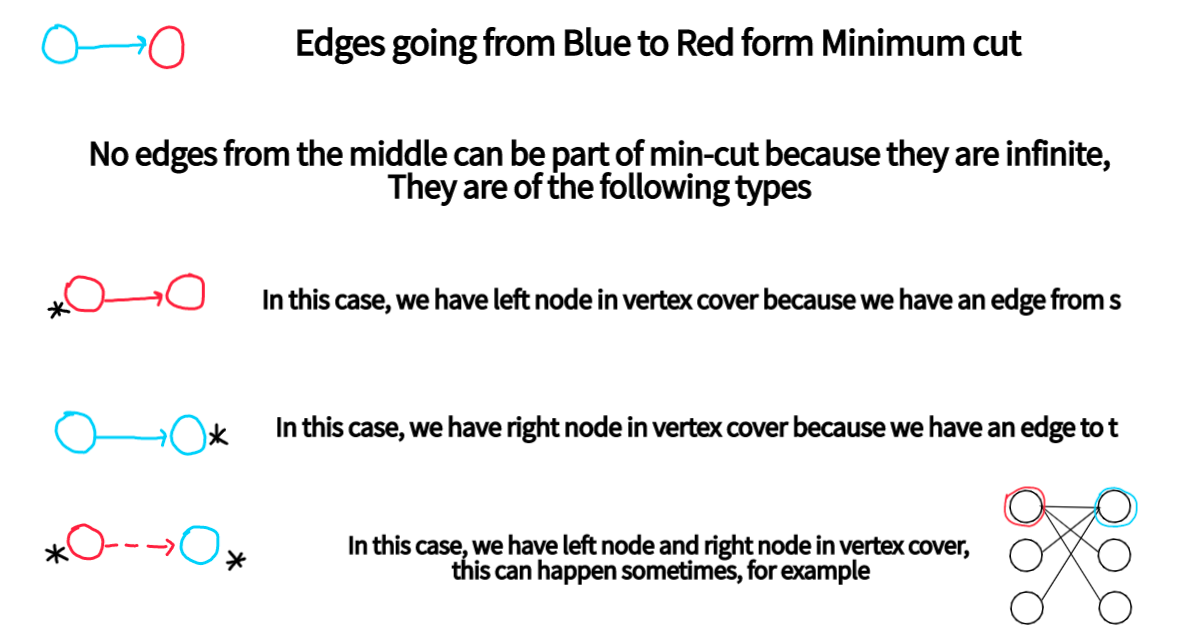

Let Z be the set of vertices reachable from s in the residual graph with maximum flow, then (L - Z) ∪ (R ∩ Z) forms minimum vertex cover. Look at the following constructive proof.

The nodes that do not belong to a minimum node cover form a maximum independent set. This is the largest possible set of nodes such that no two nodes in the set are connected with an edge. Once again, finding a maximum independent set in a general graph is a NP-hard problem, but in a bipartite graph we can use Konig’s theorem to solve the problem efficiently

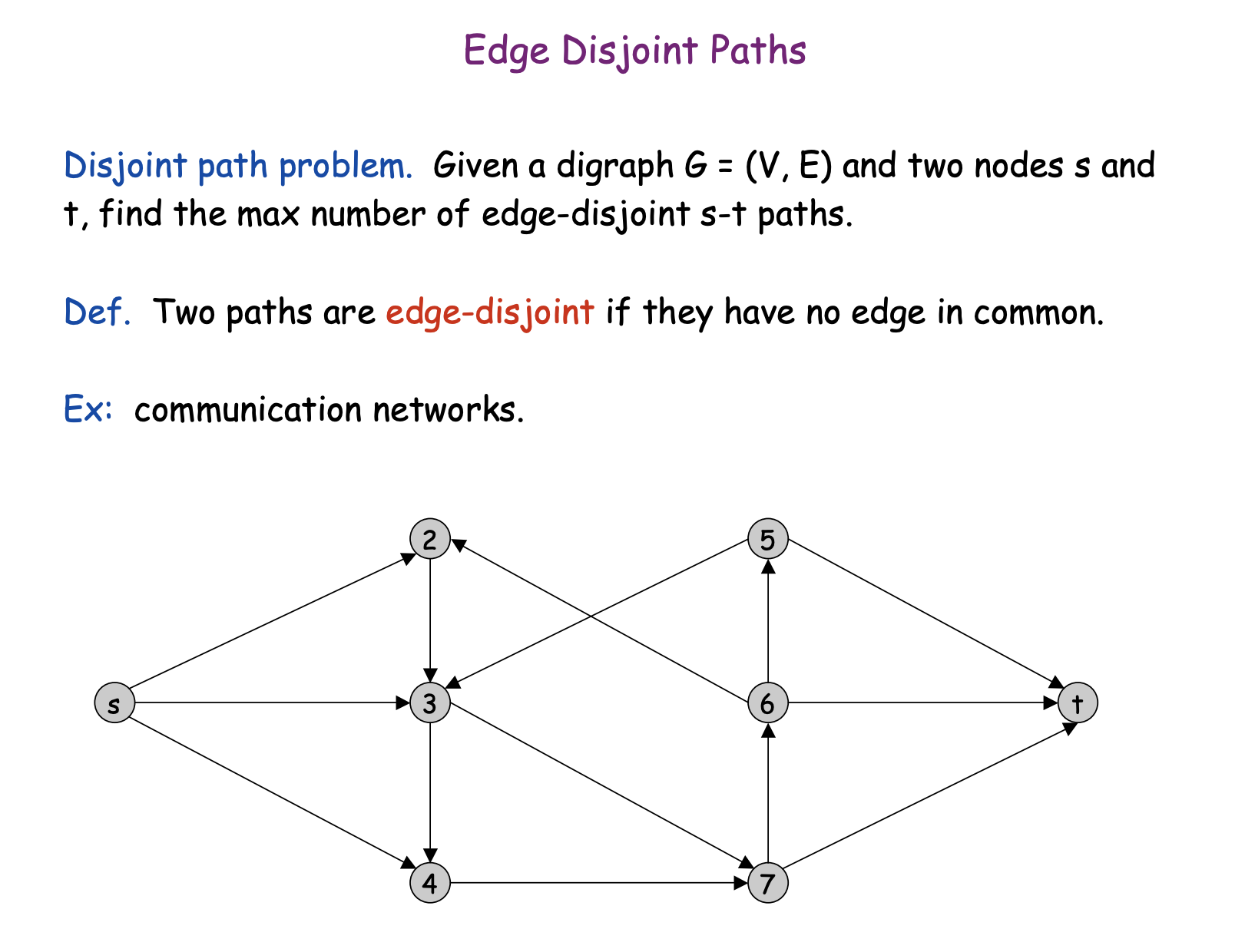

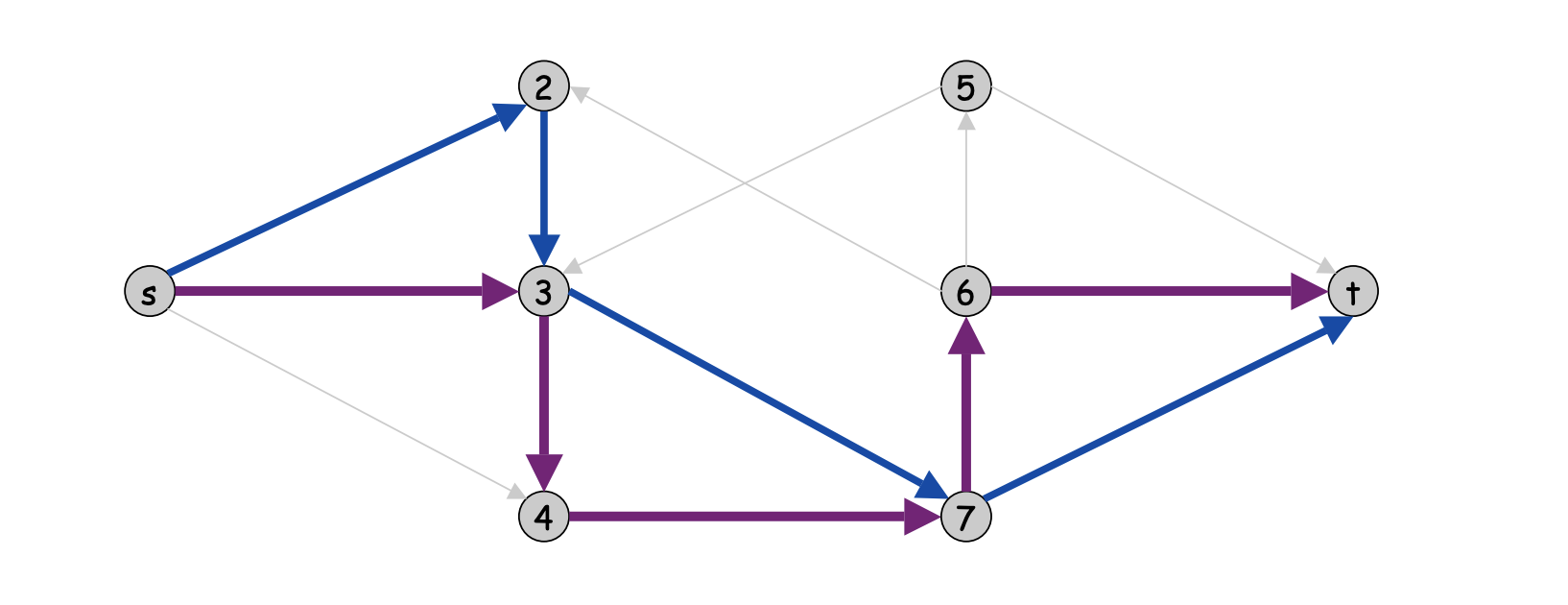

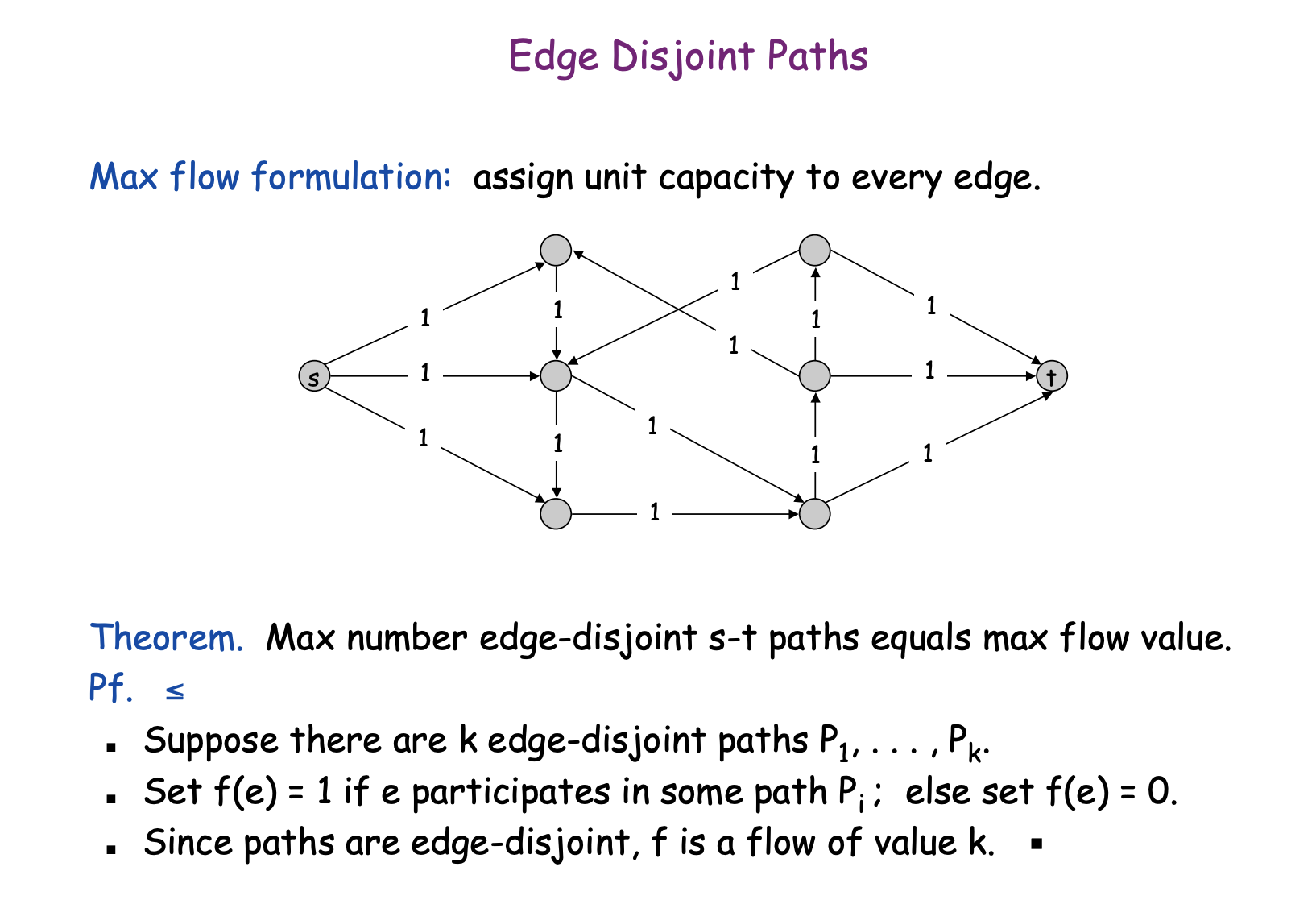

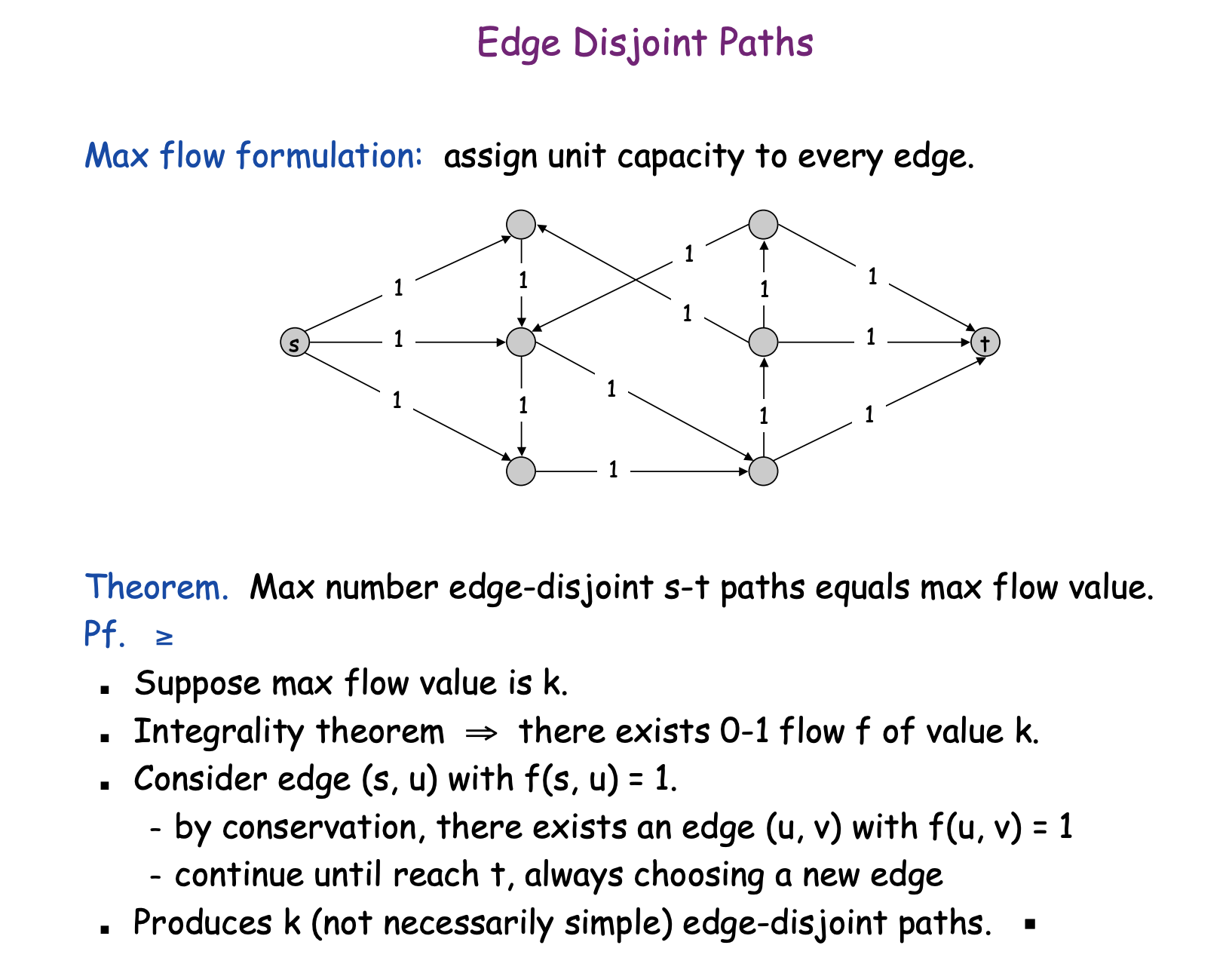

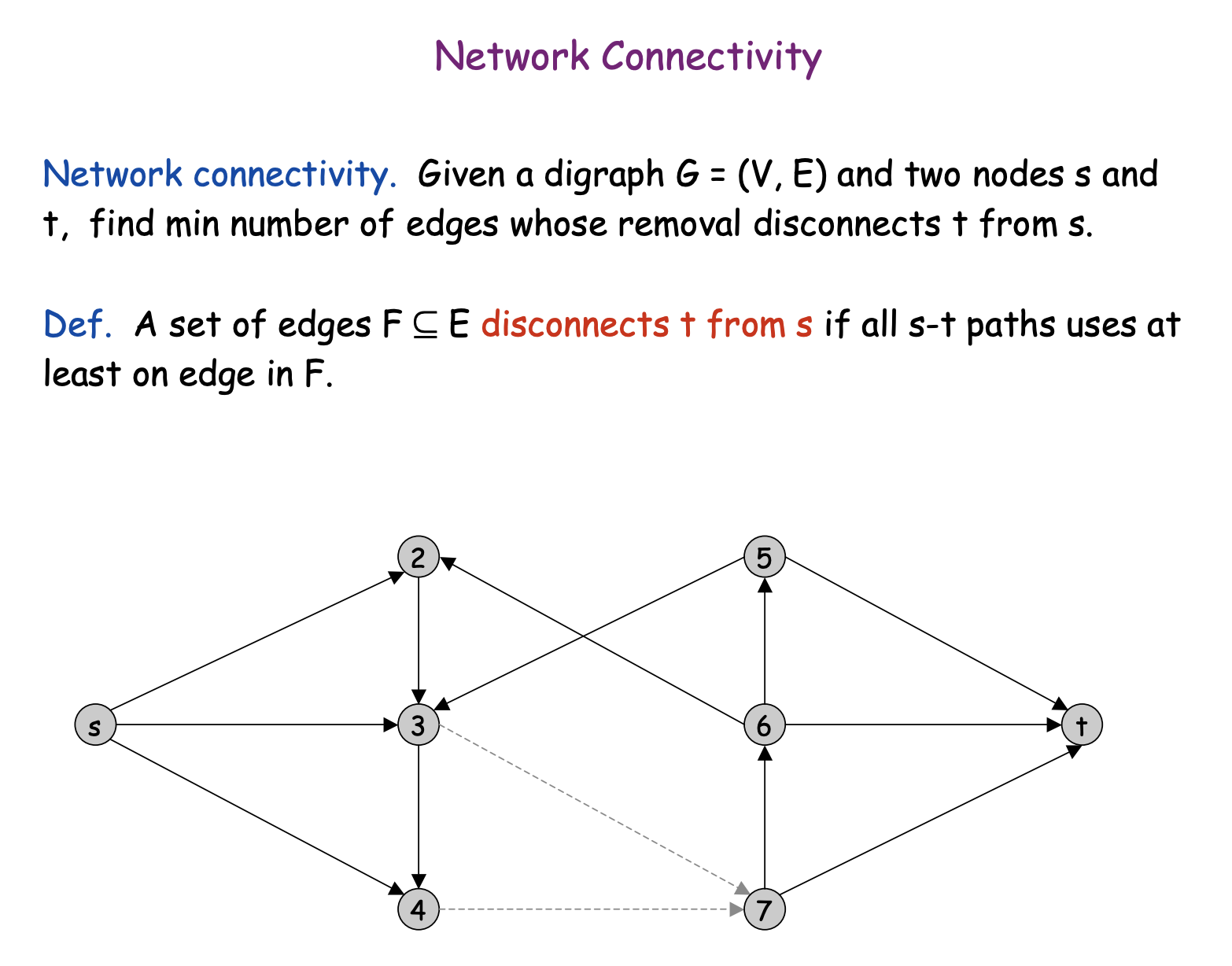

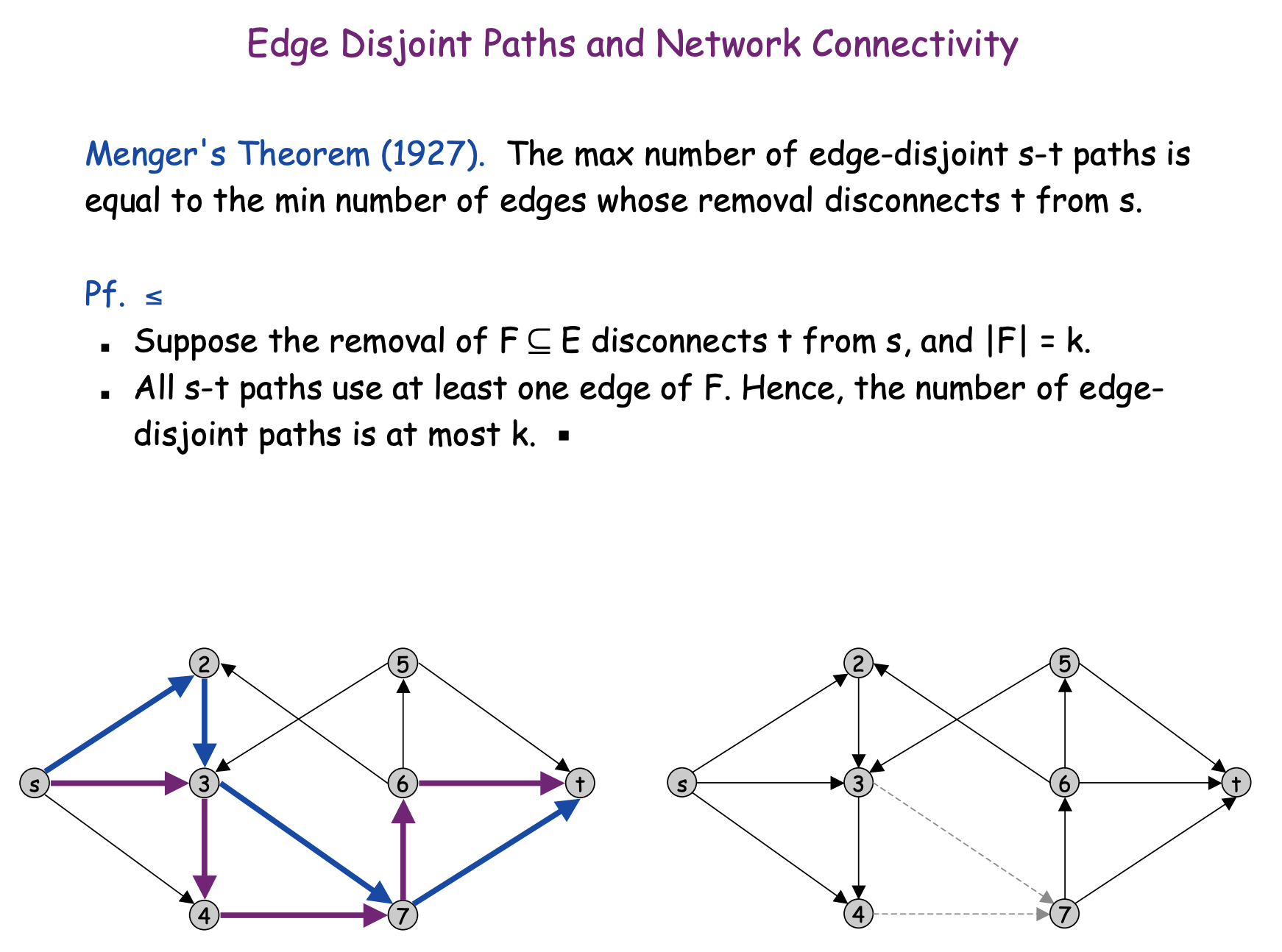

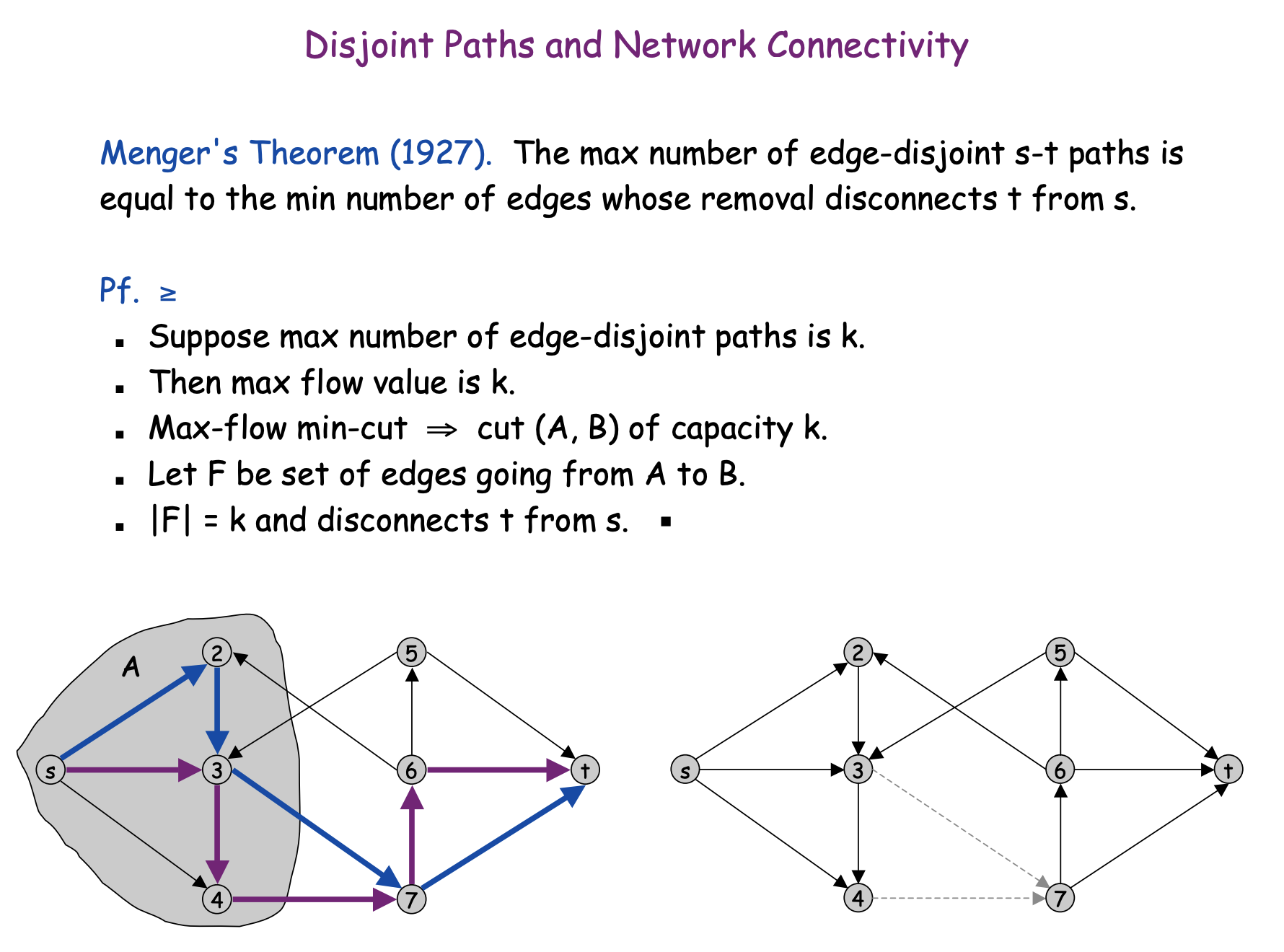

Disjoint paths

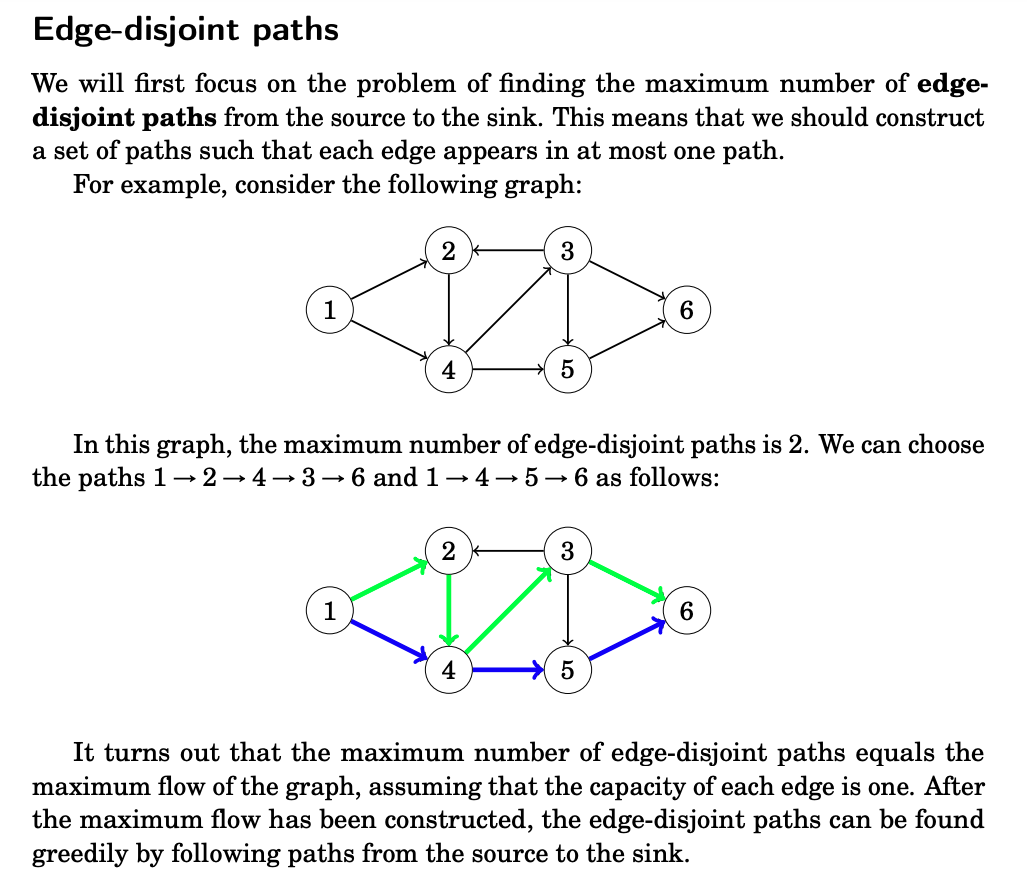

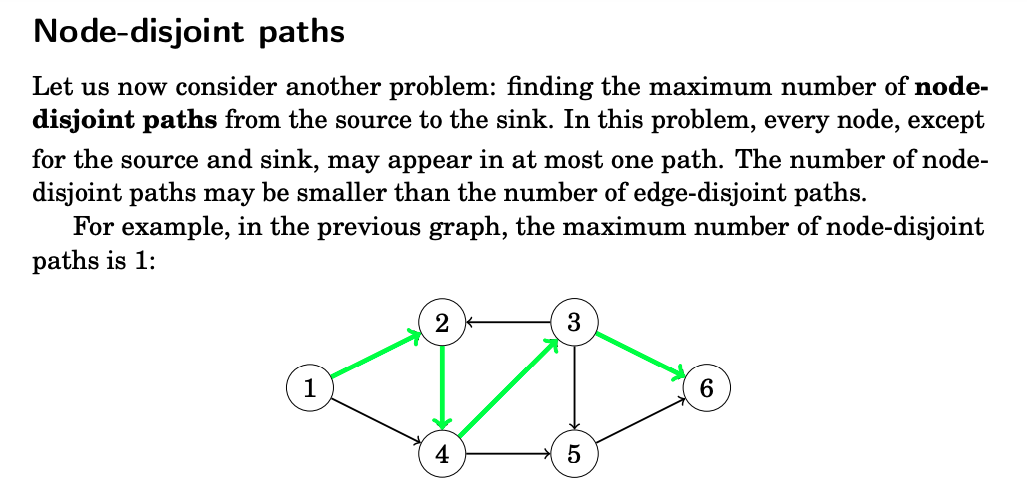

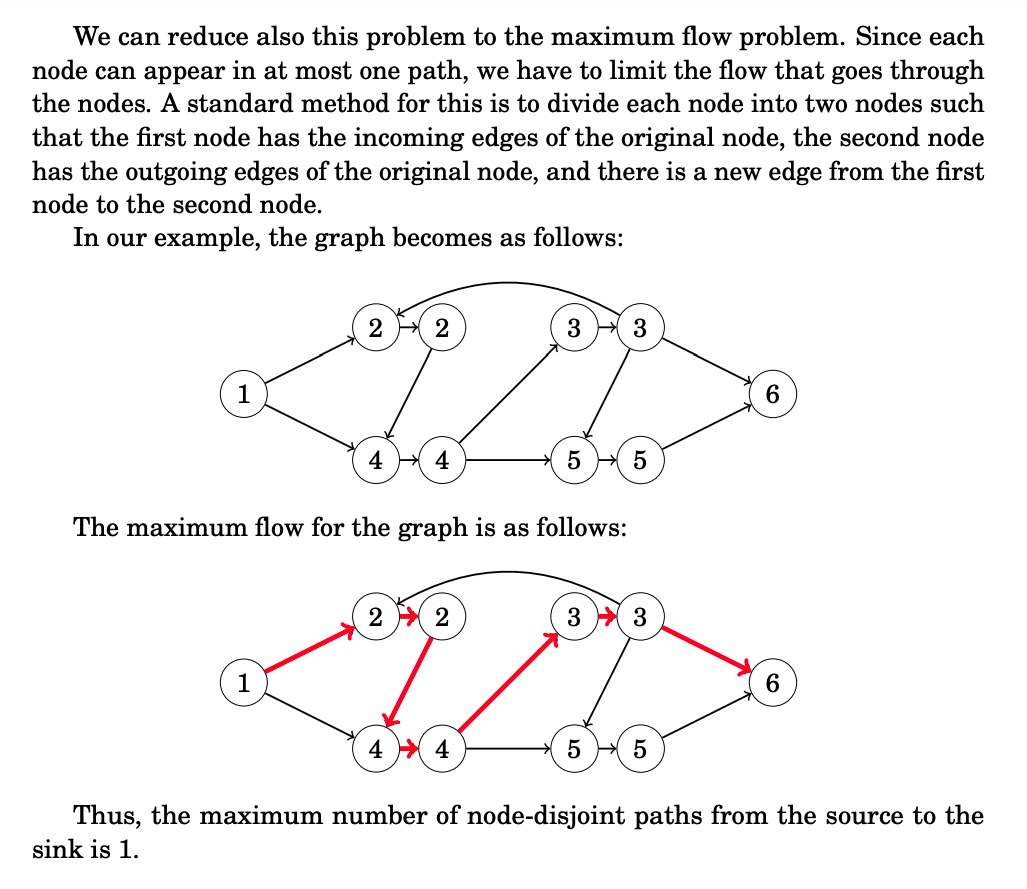

Many graph problems can be solved by reducing them to the maximum flow problem. Our first example of such a problem is as follows: we are given a directed graph with a source and a sink, and our task is to find the maximum number of disjoint paths from the source to the sink.

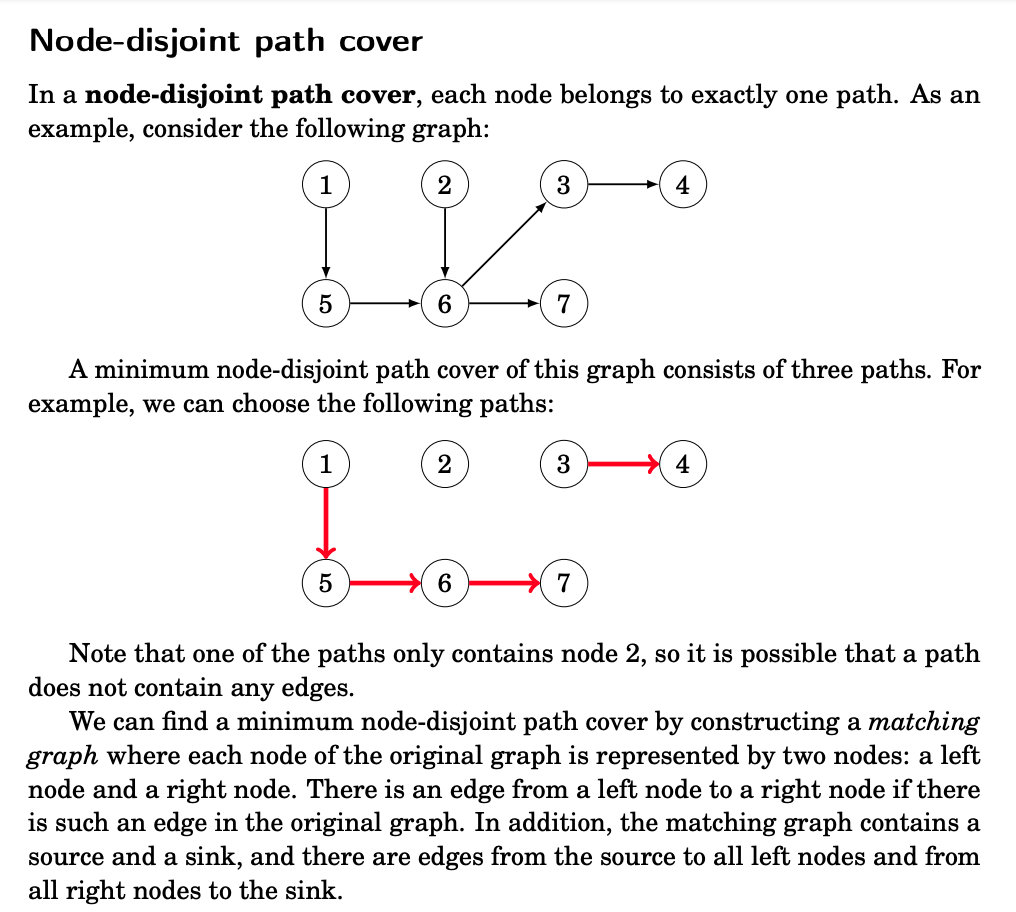

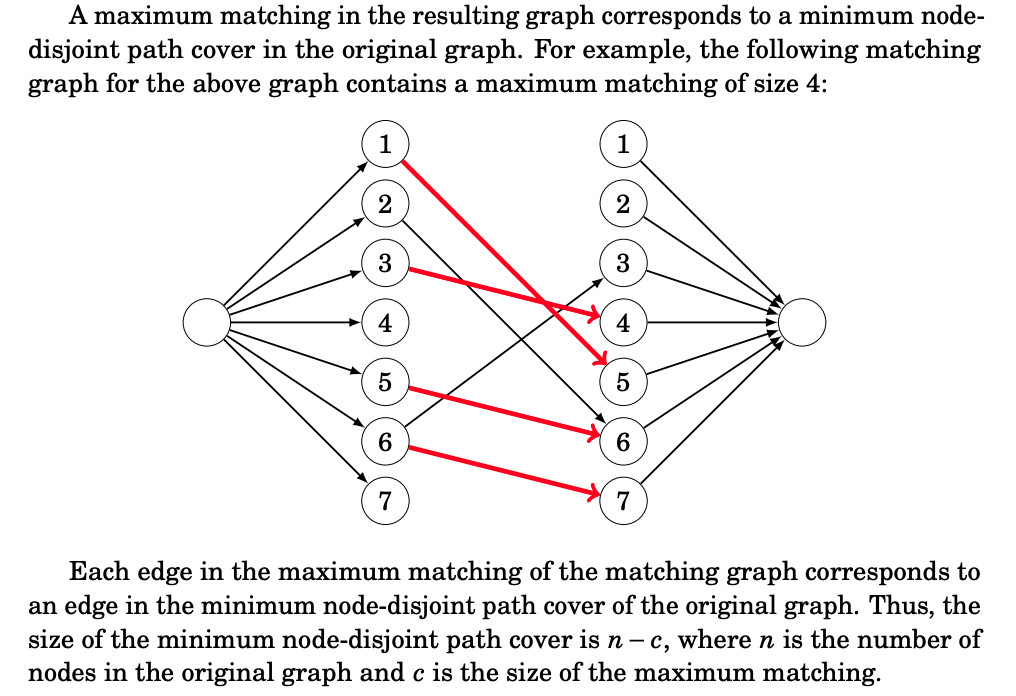

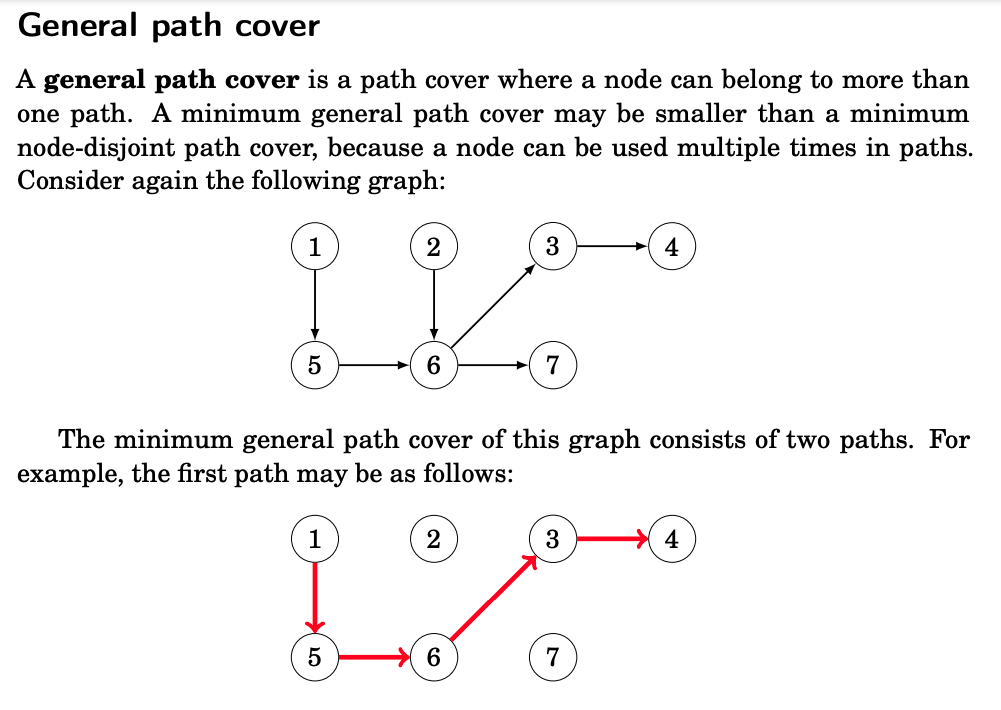

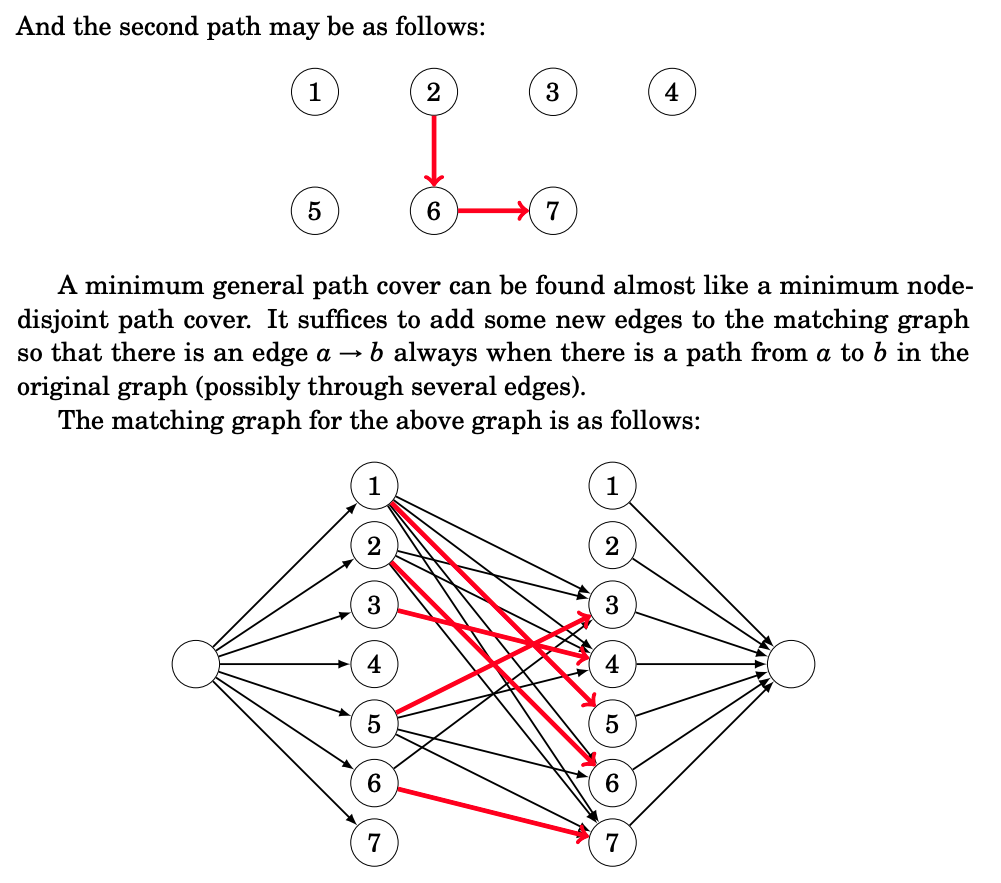

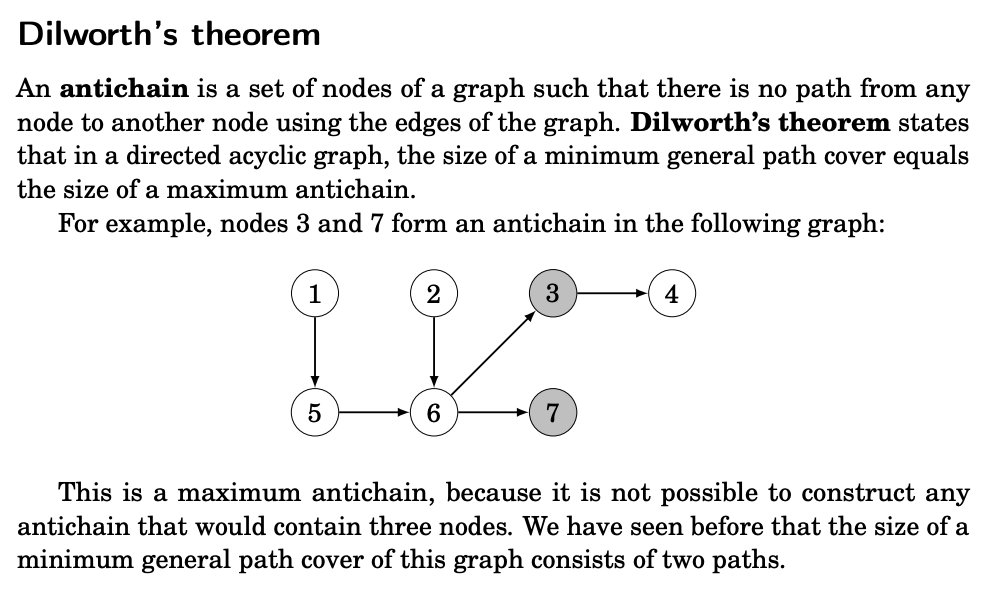

Path Covers

A path cover is a set of paths in a graph such that each node of the graph belongs to at least one path. It turns out that in directed, acyclic graphs, we can reduce the problem of finding a minimum path cover to the problem of finding a maximum flow in another graph.

Closure Problem

A closure of a directed graph is a set of vertices C, such that no edges leave C - There shouldn't be any edges going out of C, there can be edges into C. The closure problem is the task of finding the maximum-weight or minimum-weight closure in a vertex-weighted directed graph.

We are asked to find subset of V with maximum cost such that if u ∈ S and uv ∈ E => v ∈ S.

Why shouldn't we take all the vertices? Some of the costs might be negative, if all costs are positive then ofcourse we can take all the vertices.

Solution:

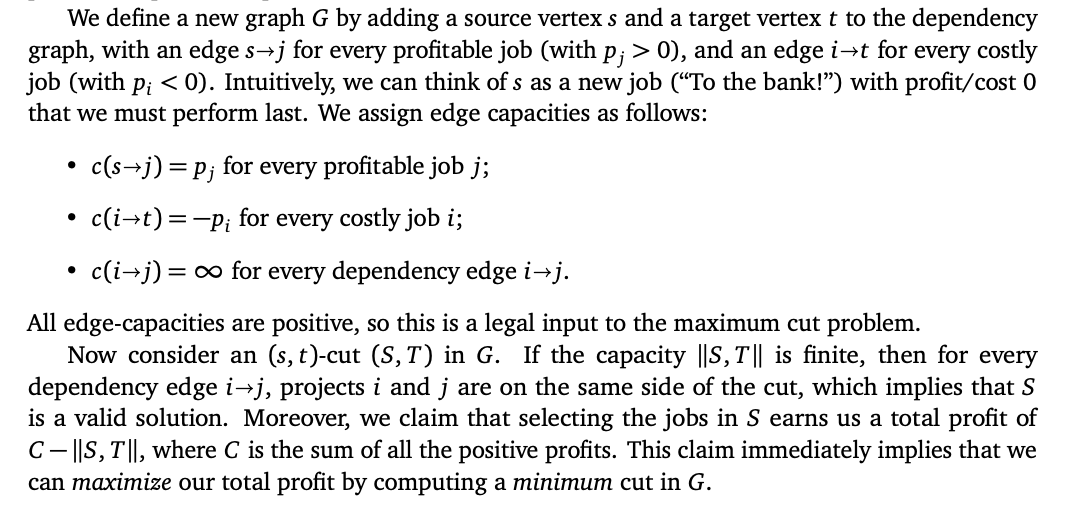

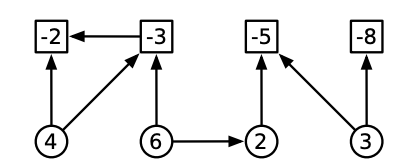

If there were no edges, what should we do? Take all vertices with positive weight.

Let's choose all the vertices with positive weight A = { v | cost(v) ≥ 0 } and exclude all the vertices with negative vertices B = { v | cost(v) < 0 }, and resolve conflicts. We either need to take negative vertices if there is a edge or exclude some positive vertices. This looks like a min-cut problem.

We cannot add negative weight edges instead we can add edges to sink. We will need to make costs positive otherwise the problem cannot be solved in polynomial time.

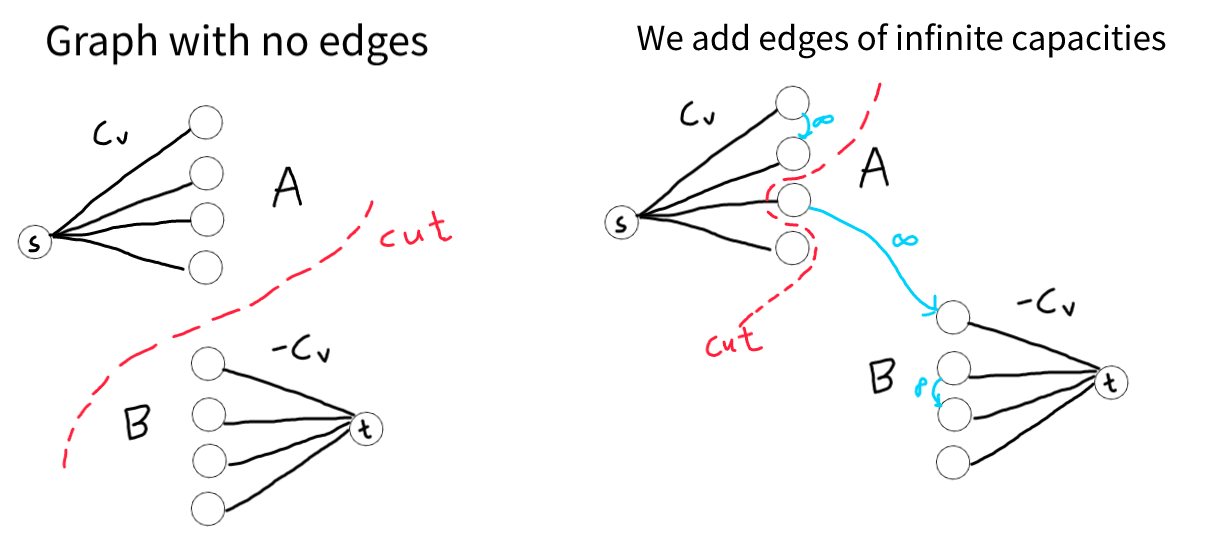

To add restrictions of choosing vertices, we add edges of inifinite capacities so that if we choose the starting vertex of edge, then the ending vertex is also present in the cut. Infinite capacity edges forbids us from putting endpoints in different cuts.

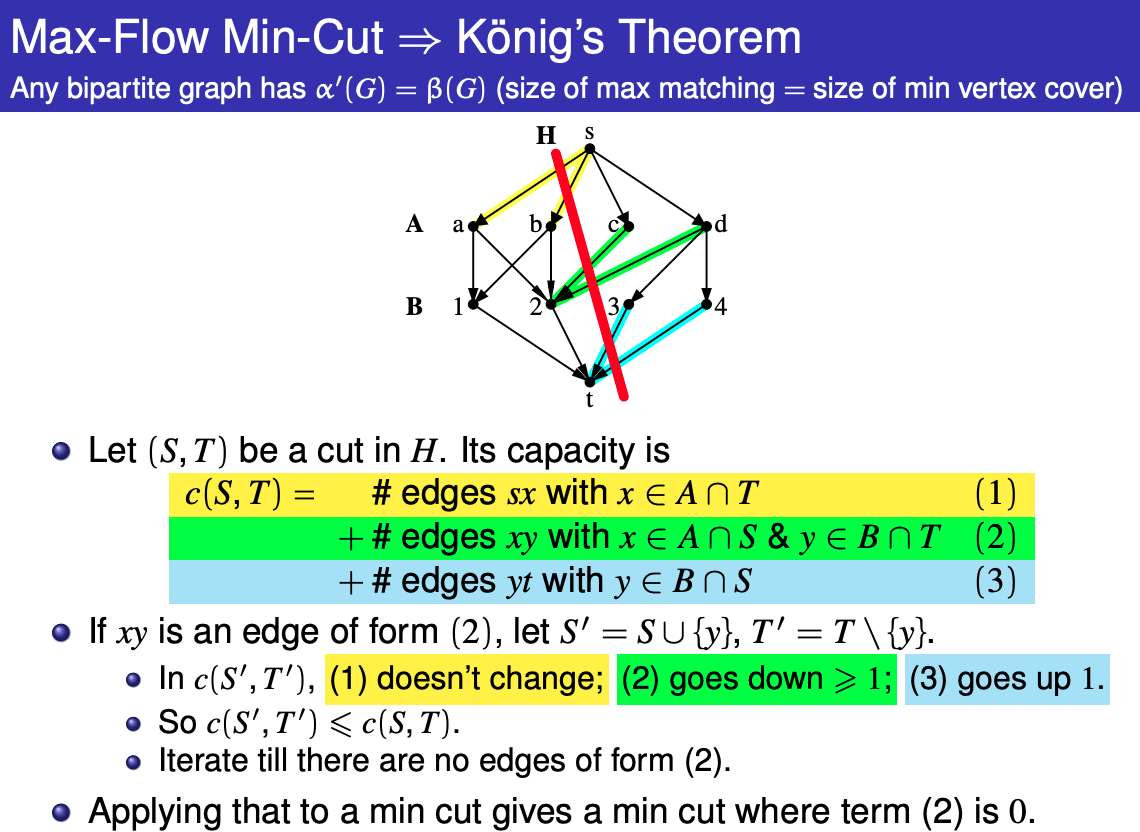

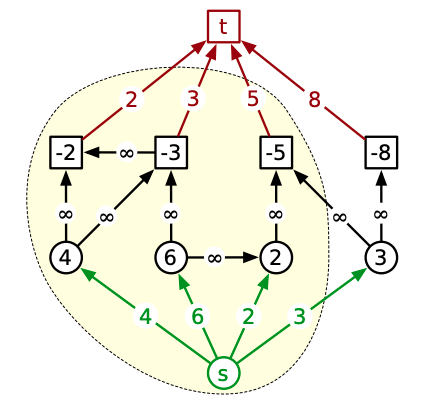

Reduction to maximum flow problem

- For each vertex

vwith positive weight inG, the augmented graphHcontains an edge fromstovwith capacity equal to the weight ofv - For each vertex v with negative weight in G, the augmented graph H contains an edge from

vtotwhose capacity is the negation of the weight ofv. - All of the edges in G are given infinite capacity in H.

A minimum cut separating s from t in this graph cannot have any edges of G passing in the forward direction across the cut: a cut with such an edge would have infinite capacity and would not be minimum. Therefore, the set of vertices on the same side of the cut as s automatically forms a closure C.

The flow network for the example dependency graph, along with its minimum cut. The cut has capacity 13 and C = 15, so the total profit for the selected jobs is 2.

How to model Minimum cut problems?

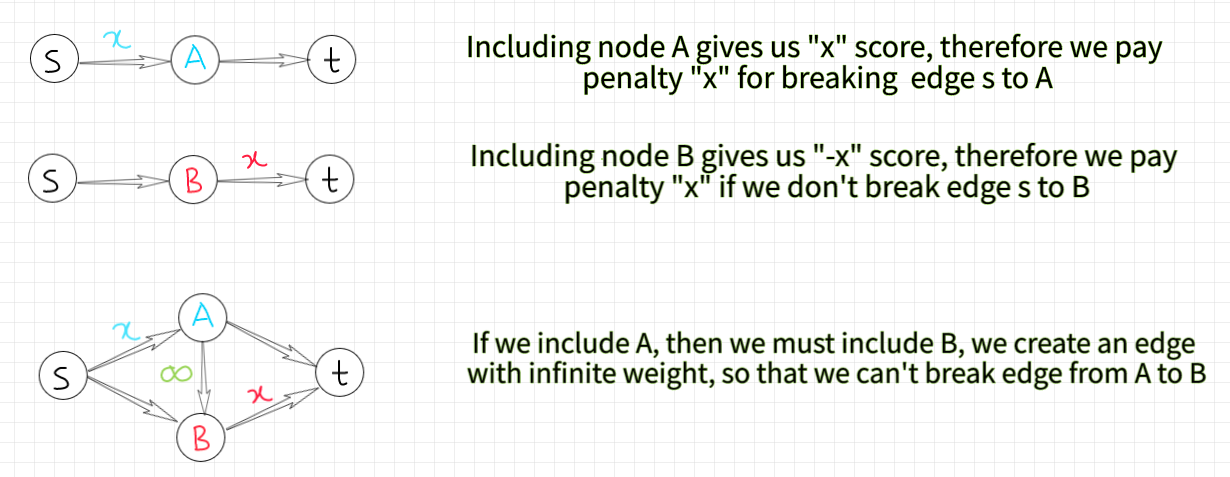

If we are given positive and negative costs/scores on nodes, then we can think in terms of penality. Firstly, we should make all the edges positives. Minimum cut tries to minimize the edge weights, hence we can think the give costs as penalities.

- Firstly, we assume that we take all the positive weight nodes, then we can think that we include positive weighted node, we will get score[x] as penality. Therefore, we draw edge from

stonodemeaning that including it gives us no penality. - For a node with negative weight, we can think that if we include it, then we have to pay penality, hence if node is part of S of s-t cut, we get penalised by weight. Therefore, we draw an edge from

nodetot. - Minimizing the cut is equivalent to minimizing the penalty.